Articles for Negative Effects of Mental Health on Families and Communities

- Review

- Open Access

- Published:

Residential schools and the effects on Indigenous health and well-being in Canada—a scoping review

Public Health Reviews volume 38, Article number:8 (2017) Cite this article

Abstruse

Groundwork

The history of residential schools has been identified as having long lasting and intergenerational effects on the physical and mental well-being of Indigenous populations in Canada. Our objective was to place the extent and range of research on residential school attendance on specific health outcomes and the populations affected.

Methods

A scoping review of the empirical peer-reviewed literature was conducted, following the methodological framework of Arksey and O'Malley (2005). For this review, ix databases were used: Bibliography of Native North Americans, Canadian Health Inquiry Collection, CINAHL, Google Scholar, Indigenous Studies Portal, PubMed, Scopus, Statistics Canada, and Web of Scientific discipline. Citations that did not focus on health and residential schoolhouse amongst a Canadian Indigenous population were excluded. Papers were coded using the following categories: Ethnic identity group, geography, age-sexual activity, residential school attendance, and wellness status.

Results

60-one articles were selected for inclusion in the review. Virtually focused on the impacts of residential schooling among First Nations, but some included Métis and Inuit. Physical health outcomes linked to residential schooling included poorer general and self-rated wellness, increased rates of chronic and infectious diseases. Furnishings on mental and emotional well-being included mental distress, depression, addictive behaviours and substance mis-use, stress, and suicidal behaviours.

Conclusion

The empirical literature can be seen every bit further documenting the negative health furnishings of residential schooling, both among former residential school attendees and subsequent generations. Futurity empirical research should focus on developing a clearer understanding of the aetiology of these effects, and particularly on identifying the characteristics that pb people and communities to be resilient to them.

Background

The effects of colonization are apparent in all aspects of Ethnic peoples' health and well-beingness [1], affecting not merely their physical wellness, but the mental, emotional, and spiritual wellness [ii]. It is well established that Indigenous peoples in Canada experience a asymmetric brunt of sick health compared to the non-Indigenous population [iii]. In large office, these wellness disparities have been a result of government policies to assimilate Ethnic peoples into the Euro-Canadian ways of life, leading to concrete and emotional harms to children, lower educational attainment, loss of civilization and language, and the disconnect of family structures [4–6]. Many of the illnesses and conditions that are unduly experienced past Indigenous peoples, including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, have therefore been attributed to the lasting effects of colonialism, including the Indian Act, the reserve organization, and residential schooling [7]. Loppie Reading and Wien [8] note that colonialism, a distal determinant of wellness, is the basis on which all other determinants (i.e. intermediate and proximal) are constructed.

Amid colonial policies, residential schooling has stood out every bit especially damaging to Indigenous peoples. The residential schoolhouse system was intended to eradicate the language, cultural traditions and spiritual beliefs of Indigenous children in order to assimilate them into the Canadian society [five, 6, 9, 10]. More than than 150,000 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children attended the church-run schools betwixt their establishment in the 1870s and the closure of the last school in the mid-1990s [11]. As admitted by regime and church officials, the explicit purpose of the residential schoolhouse arrangement was "to civilize and Christianize Ancient children" [x]. In improver to the cultural and social furnishings of existence forcibly displaced, many children suffered physical, sexual, psychological, and/or spiritual abuse while attending the schools, which has had indelible effects including, health problems, substance corruption, mortality/suicide rates, criminal activeness, and disintegration of families and communities [five]. Moreover, many of the residential schools were severely underfunded, providing poor nutrition and living conditions for children in their care, leading to illness and death [v].

These attempts of forced assimilation have failed, in part due to the resilience and resistance of many Indigenous communities [12]. Withal, it is credible that they have had profound effects "at every level of experience from private identity and mental wellness, to the structure and integrity of families, communities, bands and nations" [vi]. The concept of historical trauma suggests that the effects of these disruptive historical events are collective, affecting not but private Survivors, but also their families and communities [13, 14]. According to Kirmayer, Gone, and Moses, historical trauma provides a fashion to conceptualize the transgenerational effects of residential schooling, whereby "traumatic events endured by communities negatively touch on on private lives in ways that result in hereafter issues for their descendants" [xiv]. Recent findings suggest that the effects of the residential school system are indeed intergenerational, with children of attendees demonstrating poorer wellness status than children of non-attendees [9]. In fact, families in which multiple generations nourish residential schools take been found to have greater distress than those in which merely one generation attended [9]. Although this provides of import evidence of the role of residential schooling in the current health and social conditions of Indigenous peoples, the links in the causal chain are non well understood, and there are many potential intermediate factors between residential schoolhouse attendance and its effects on subsequent generations [fourteen].

The consequences of residential schooling for Indigenous peoples in Canada have been known for some time, having been documented by the accounts of former attendees [15, 16]. These effects parallel experiences in the USA and Australia, where boarding or residential schools were as well a key tool of assimilation [17]. In its final report, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada made 94 "calls to activeness" to redress the legacy of residential schools [xviii]. Amidst those related to health, the TRC admonished federal, provincial and territorial levels of government to admit the effects of Canadian government policies (e.grand. residential schools) and, working together with Ethnic peoples, to place and close the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities in health outcomes [18]. Although in that location accept been some empirical studies of the effects of residential schooling on Indigenous peoples' health, at that place has been no previous endeavour to synthesize the evidence of these effects. The purpose of this scoping review is therefore to describe the current state of the literature regarding residential school omnipresence and the wellness and well-being of Ethnic people in Canada. In particular we ask; what are the health outcomes that have been empirically linked to residential schooling, what are the populations in which these effects accept been identified, and whether effects are found among Survivors or likewise amidst other family members and subsequent generations. By summarizing the current literature and identifying needs for further research, this effort can contribute to our understanding of the effects of residential schooling on the wellness and wellness of Indigenous peoples.

Methods

Search strategies

The scoping review process for this newspaper was informed by Arksey and O'Malley's methodological framework for scoping studies [nineteen]. A scoping review is an arroyo used to map the existing literature on a particular general topic in society to understand the overall state of knowledge in an area [nineteen]. Scoping studies therefore typically have broad research questions and focus on summarizing the available show [20]. According to Armstrong and colleagues, a scoping review as well differs from a systematic review in that the inclusion/exclusion criteria can be developed in an iterative process, the quality of studies might not be discussed in the review, and that the synthesis tends to be more qualitative in nature with the review used to identify parameters and gaps in a torso of literature rather than coming to a conclusion about the bear witness for a specific outcome or effects [21]. Although a scoping review may not draw research findings in detail, it provides a style of navigating the area of research where the range of cloth is uncertain [19]. Arksey and O'Malley suggest v stages in conducting a scoping review: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (three) report selection, (4) charting the data, and (v) collating, summarizing and reporting the results [nineteen]. These five stages were used to inform and guide the current literature review. The intent of this scoping review was to assess the extent and range of empirical inquiry examining residential schooling and wellness outcomes amid Indigenous peoples. This broad research question was established at the beginning and was used to guide the subsequent stages of the review. In society to identify relevant literature, we conducted a search of nine electronic databases: Bibliography of Native N Americans, Canadian Health Enquiry Collection, CINAHL, Google Scholar, Indigenous Studies Portal, PubMed, Scopus, Statistic Canada, and Web of Scientific discipline. The search strategy and search terms were developed with the assist of an academic librarian who specializes in First Nations studies. Wide search terms were used within these databases and are documented in Table 1.

The search results were downloaded into the reference direction software Endnote (Endnote X7, Thomson Reuters, 2014), from which duplicates were removed. Inclusion was determined using the following criteria: (a) English-language source (or translated abstract), (b) analysis using principal or secondary data, (c) focus on an Indigenous population in Canada (e.thou., First Nations, Inuit, Métis), and (d) focuses on residential school attendance and its relation to wellness. Grey literature addressing residential school omnipresence and health were likewise sought out to provide additional back up, including government or arrangement reports, commentaries, or news bulletins.

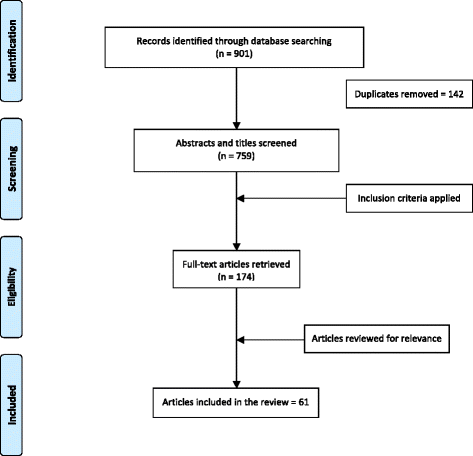

Selecting the articles for inclusion was completed in ii steps. In the first stage, ii reviewers screened titles and abstracts and citations that did not meet the inclusion criteria were removed. If the reviewers were unsure about the relevancy of an abstract, the full text of the article was retrieved and reviewed. At the 2d phase, the full texts of the articles were reviewed for final inclusion. The bibliographies of the total articles were hand-searched to place further relevant references. Systematic or scoping reviews were not included in this scoping review; however, their reference lists were reviewed for pertinent references. A detailed chart depicting the search results is provided (Fig. 1). Following Arksey and O'Malley's framework [19], a spreadsheet was created to chart the relevant data that is pertinent to the research question. The papers selected for inclusion were coded following similar categories used by Wilson and Young [22] and Young [23] in their reviews of Indigenous health research. The categories used includes: Indigenous identity group, geographic location, age-sex, residential schoolhouse omnipresence, and wellness status. A description of each category is provided beneath. Data extraction was carried out past one of the researchers in an Excel database and was verified by some other team member.

Scoping review search results

Classification categories

Studies were classified according to the health outcomes examined, the Indigenous population affected, the geographic location of the study, and the historic period and sex activity/gender categories included in the written report, and the type of residential schooling effect investigated.

Health outcomes

Although we distinguish specific types of wellness outcomes resulting from personal experiences and the intergenerational impacts of residential schooling, information technology is important to admit that these outcomes do not occur independently, but be in circuitous relationships with other furnishings [24]. The consequences of residential schools are broad-reaching and, co-ordinate to Stout and Peters [24], may include, "medical and psychosomatic weather condition, mental health bug and mail traumatic stress disorder, cultural effects such as changes to spiritual practices, diminishment of languages and traditional knowledge, social effects such as violence, suicide, and effects on gender roles, childrearing, and family relationships". Social, cultural, and spiritual effects of residential schools are often associated with physical, mental, and emotional health [24]. For the purposes of categorizing the types of outcomes described in the studies reviewed, it was necessary to impose somewhat capricious categories of physical health, mental health and emotional well-being, and general health, every bit described below.

- (1)

Physical health: Wellness atmospheric condition may include arthritis, chronic back hurting, rheumatism, osteoporosis, asthma, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, allergies, cataracts, glaucoma, blindness or serious vision problems that could not be corrected with spectacles, epilepsy, cerebral or mental disability, heart affliction, high blood pressure level, furnishings of stroke (encephalon hemorrhage), thyroid bug, cancer, liver disease (excluding hepatitis), stomach or intestinal bug, HIV/AIDS, hepatitis, tuberculosis, or diabetes [25].

- (ii)

Mental health/emotional well-existence: Mental wellness issues may include depression, anxiety, substance abuse (east.one thousand. drugs or booze), paranoia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sexual dysfunction, personality disorders, stress, effects on interpersonal relationships, psychological or nervous disorders, and attention deficit disorder/attention inability. In addition, for the purposes of this review, suicide and suicide attempts or thoughts were too classified with mental health.

- (iii)

General health: A category related to full general overall health was also included for papers that did not brand references to a specific health outcome.

Ethnic identity grouping

Populations were too classified equally either referring to a single Ethnic identity (Outset Nations, Métis, or Inuit) or a combination of identities (a combination of two single identity groups, or Indigenous and non-Ethnic identities).

Geographic location

For this review, we examined two aspects of geography. Firstly, we determined if the studies referred to Indigenous populations living on Showtime Nations reserves, Footnote 1 Northern communities, not-reserve rural areas, or in urban areas. Secondly, we identified the province or territory of focus in the paper.

Age-sex/gender categories

The health outcomes associated with residential school omnipresence might be different for men and women, or boys and girls. Studies were categorized by the age range and sex activity/gender of the participants.

Residential schoolhouse omnipresence

Residential school omnipresence was classified as either personal omnipresence or familial attendance (i.e. parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles).

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

Every bit depicted in Fig. ane, 61 studies were institute that discussed residential schools in Canada and the health effects among Survivors, their families, or communities. The details of each study included in the review were provided in a chart and tin can be found in Table 2. The majority of papers were published in 2000 and after, with the exception of one published in 1999. Their sample sizes ranged from 1 to 51,080 and involved children, youth, and adults. Ofttimes, studies included men and women, various Ethnic identities, several geographic locations, and personal and familial residential schoolhouse attendance.

Indigenous identity group

The majority of studies, 43, included Showtime Nations. Xviii studies involved Inuit and 17 included Métis. In xi, the population was identified as "Ancient" or "Indigenous" and did not distinguish between Start Nations, Inuit, or Métis. Three studies too included "Other" Indigenous populations that were not further divers, two included multiple identities, one undisclosed identity, and two included non-Canadian Ethnic populations (Sami, American Indian).

Geographic location

A total of 14 studies were conducted using national level Canadian data. 7 studies focused on Atlantic Canada; two were conducted in Newfoundland, one in Nova Scotia, one in New Brunswick, and two in the Atlantic region. Half dozen studies were conducted in Quebec, x studies took place in Ontario, and one in Key Canada. In Western Canada, eight studies took place in Manitoba, eight in Saskatchewan, ten in Alberta, xiii in British Columbia, 1 in the prairies, and three in Western Canada. Additionally, a few studies were conducted in the territories, with ii taking identify in the Northwest Territories, and half dozen in Nunavut. 2 studies did not specify a geographic location and ii were conducted in the The states.

Xx-four studies considered Indigenous peoples living on-reserve, while 23 involved those living off-reserve. Study participants living off-reserve can be further categorized every bit living in rural or remote areas, northern communities, or urban areas. Seventeen studies indicated that their participants were from a rural or remote location, xiv included participants in northern communities, and 24 focused on urban populations.

Age-sex/gender

Both males and females were represented in the enquiry with 48 studies including both men and women. V studies included only women, and i solely looked at males. Also, one study included participants who are transgender, one written report indicated "other", and 3 did non provide a description of the participants' sex or gender. Regarding age, 46 studies included individuals over the historic period of xviii, whereas 15 included children and youth under the age of 18. Nine studies did not include information on the age of participants.

Residential school attendance

In terms of residential school attendance, 42 of the studies reviewed included residential school attendees themselves (personal attendance) and 38 examined the effects of having a parent or other family members who had attended (familial attendance). Four studies did non indicate who had attended residential school.

Health outcomes

General health: It is evident from the results of this review that personal or familial (e.chiliad. parental or grandparental) residential schoolhouse attendance is related to health in a multitude of ways. Twelve papers used self-reported health or general quality of life as an outcome measure and establish that people who had attended residential schools more often than not felt as though their health or quality of life had been negatively impacted. Using Statistics Canada's 2001 Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS), Wilson and colleagues establish that those who had attended residential schools had poorer overall self-rated wellness than those who did non attend [26], a finding that was reproduced with the 2006 APS past Kaspar [27], who constitute that 12% of those who had attended residential schoolhouse reported poor wellness, compared with 7% of those who did not attend. While this may exist attributed to other factors such as aging inside the population, the role of residential schools cannot be dismissed [26]. Hackett et al. found that familial omnipresence at residential school was associated with lower likelihood of reporting excellent perceived health, fifty-fifty after decision-making for covariates such as health behaviours, issues with nutrient security and/or housing [28] However, while the studies reveal negative furnishings in relation to the residential school organisation, this cannot be said for everyone who attended. For example, some studies take establish improve overall reported wellness among those with family members who attended (see, e.k. Feir [29]). Concrete wellness: Physical health problems, namely chronic wellness conditions and infectious diseases, were besides apparent in the literature. Thirteen papers related specific physical health conditions to residential school attendance. These included conditions such every bit HIV/AIDS, chronic atmospheric condition (e.thousand. diabetes, obesity), tuberculosis (TB), Hepatitis C virus (HCV), chronic headaches, arthritis, allergies, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In a study by Ghosh [thirty], participants stated that their experiences at residential schoolhouse impacted their diets through the higher consumption of carbohydrates, a factor the authors relate to the higher rates of diabetes among this population today. Howard [31] plant like results and suggested that residential schooling contributed to the urbanization of Indigenous peoples in Canada, which has led to diabetes and other problems. Dyck and colleagues also reported that those who attended residential school had a slightly higher prevalence of diabetes than those who did not, although the finding was not statistically significant [32]. Residential school omnipresence has as well been found to be a positive predictor of obesity amongst younger Métis boys and girls, but a negative predictor amongst older girls [33]. In addition to chronic atmospheric condition, residential school omnipresence has been associated with poorer sexual health in general [34, 35], infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS and STIs [36] and has been identified as an independent risk factor for HCV [37]. Corrado and Cohen establish that many First Nations people who had personally attended residential schools reported suffering from physical ailments including, chronic headaches, centre problems, and arthritis [five].

Mental wellness and emotional well-being: Mental health, and particularly emotional well-existence, was the area of health about commonly identified as affected past residential school omnipresence. Forty-3 studies reviewed found that personal or intergenerational residential school attendance was related to mental health issues such as mental distress, depression, addictive behaviours and substance misuse, stress, and suicidal behaviours. For example, Walls and Whitbeck [38] noted that early lifetime stressors such as residential school attendance are negatively associated with mental wellness among adults. Corrado and Cohen [5] found that among 127 residential school Survivors, all but two suffered from mental health problems such as PTSD, substance abuse disorder, major depression, and dysthymic disorder. These authors advise that residential school leads to a specific combination of furnishings a—"Residential School Syndrome". Anderson [39] found that residential schoolhouse attendance amidst Inuit men was related to mental distress. Familial residential school attendance has been associated with lower self-perceived mental wellness and a higher gamble of distress and suicidal behaviours [28]. Intergenerational effects were found by Stout [xl] amongst women who had parents or grandparents attend residential schools, with women reporting that familial attendance at residential school had had an enduring impact on their lives and mental wellness.

Substance abuse and addictive behaviours have too been identified equally mutual amidst those impacted by residential schools. In a study conducted by Varcoe and Dick [36], a participant associates her drinking and drug use to the sexual, physical, emotional, and mental abuse experienced at residential school. Similarly, co-researchers (research participants) in two studies explained their addiction to drugs and booze as a "coping mechanism" [44, 54].

Suicide and suicidal thoughts and attempts were associated with personal and familial residential schoolhouse attendance in several papers. Elias and colleagues [41] found that residential schoolhouse attendees who suffered abuse were more than likely to have a history of suicide attempts or thoughts. Furthermore, non-attendees who had a history of abuse were more than likely to report having familial residential school omnipresence, suggesting that residential schooling might be important in the perpetuation of a cycle of victimization. Youth (12–17 years) participating in the on-reserve Get-go Nations Regional Health Survey who had at least ane parent who attended residential school reported increased suicidal thoughts compared to those without a parent that attended [42].

Discussion

This review aimed to summarize the current literature on residential schools and Indigenous health and well-being using Arksey and O'Malley'due south scoping review framework [19]. In general, the empirical literature further documented the wide ranging negative effects of residential schools that had previously been identified by Survivors themselves [xv] and confirmed that residential schooling is likely an important contributor to the electric current wellness conditions of Indigenous populations in Canada. The studies included revealed a range of poorer physical, mental and emotional, and general health outcomes in both residential school attendees and their families compared with those without these experiences. This included evidence of poorer full general health, higher risk of chronic conditions such as diabetes, as well as infectious diseases such as STIs. Many of the studies related residential schooling to poorer mental health, including depressions and substance misuse. Although the majority of studies focused on First Nations, various effects were observed among Métis and Inuit too, and in urban, rural and reserve populations, and in all regions, strongly suggesting that the effects of residential schooling are felt past Indigenous peoples across Canada. The regional and historical variations in the implementation of residential schooling [10] would atomic number 82 us to expect geographic variability in these furnishings. While only one study reviewed examined these differences, it is indicated that variation in health status among community members may exist related to various colonial histories in dissimilar areas [43]. Chiefly, given the vast consequences and predominately negative impact of omnipresence at these schools, the literature reviewed suggests that younger generations continue to feel the negative wellness consequences associated with residential schooling. Some of the papers were able to identify specific intergenerational effects, including higher hazard of negative outcomes for those whose parents or grandparents attended, whether they themselves were residential school Survivors [9]. Others only considered whether family members had attended, suggesting that the effects are clustered within families, rather than isolating the intergenerational transmission of trauma related to residential schooling.

Overall, the newness of the literature indicates that this is a contempo and growing area of research. One of the likely consequences of this is that much of the enquiry reviewed was correlational, and few studies explicitly examined the mechanisms that connected residential school feel to health outcomes. Although some of the studies examining mental health identified substance apply resulting from a demand to cope with psychological pain [44, 45, 54] or to provide individuals with feelings of regaining power and control [45], well-nigh of the studies of concrete wellness effects or general health did non attempt to unpack the range of proximate and mediating factors in the causal concatenation between residential schooling and the wellness of Survivors or of their family members.

A strength of this review is that it was conducted systematically and provides methodological accounts to ensure the transparency of the findings. Additionally, the findings of this enquiry highlight the extent and range of the available literature on this of import topic in health and advise areas that require further inquiry. Information technology is important to acknowledge its limitations, still. Firstly, while a scoping review provides a rapid summary of a range of literature, it does not include an appraisal of the quality of the studies included nor provide a synthesis of the data. Secondly, the inclusion of studies is determined by the reviewer's interpretation of the literature and therefore may be more subjective in nature.

Implications

The lasting effects of residential schooling on the current Ethnic population are complicated and stretch through time and across generations. It is clear, though, that our agreement of the factors that affect Indigenous peoples' health should include both the effects of "early, colonization-specific" experiences [27] besides as the more proximate factors, including socioeconomic disadvantages and community weather condition [27]. Although this complexity and the affect of colonial policies and practices, such equally residential schooling, on other determinants, such equally income, education, and housing has been noted [8], there is a need to establish a more than comprehensive understanding of the implications of this historical trauma, and particularly of the mechanisms by which intergenerational trauma continues to affect Ethnic peoples' well-being, including the enduring furnishings across generations [46].

This would include more enquiry that examines how the furnishings of residential schooling are mediated or moderated by other social and cultural determinants. For case, the utilize of ecological frameworks would help researchers and health professionals gain a deeper understanding of how the various levels of context in which the high rates of diseases such as obesity and diabetes have developed have themselves been shaped past colonial policies and by residential schooling in item. Although isolating the furnishings of residential schooling on health is of import, future empirical assay should also examine the possible cumulative effects of stressors and traumas, and how these might contribute to the standing difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples' health status [46].

Conclusions

The findings from this scoping review highlight the importance of considering authorities policies and historical context as critical to understanding the contemporary wellness and well-existence of Ethnic peoples. As Kirmayer, Tait and Simpson [47] annotation, this includes other colonial policies, forms of cultural oppression, loss of autonomy, and disruption of traditional life, equally well as residential schooling. Improve cognition of how the effects of these historically traumatic events proceed to affect communities and individuals may help inform both population health interventions and the care and treatment of individuals. Moreover, identifying the characteristics and weather of those individuals and communities who accept been resilient to the furnishings of residential schooling may contribute to promoting appropriate supports to limit the transmission of these effects.

Notes

-

In Canada, "Reserves" are parcels of Crown land set aside for utilize past particular Kickoff Nations communities.

Abbreviations

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- IDU:

-

Injection drug user

- PTSD:

-

Post traumatic stress disorder

- STIs:

-

Sexually transmitted infections

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

References

-

Gracey Grand, King M. Indigenous wellness part i: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):65–75.

-

National Aboriginal Wellness Organization. Ways of knowing: A framework for health research. 2003. p. one–29.

-

Adelson North. The embodiment of inequity: health disparities in aboriginal Canada. J Public Health. 2005;96 Suppl 2:S45–61.

-

Reading J, Elias B. Chapter 2—an examination of residential schools and elder health. In: Showtime Nations and Inuit Health Survey, Starting time Nations and Inuit Regional Health Survey National Steering Committee. 1999.

-

Corrado RR, Cohen IM. Mental Health Profiles for a Sample of British Columbia's Aboriginal Survivors of the Canadian Residential Schoolhouse System. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation; 2003.

-

Kirmayer LJ, Simpson C, Cargo K. Healing traditions: civilisation, customs and mental health promotion with Canadian aboriginal peoples. Australas Psychiatry. 2003;11(Suppl1):S15–23.

-

Bodirsky M, Johnson J. Decolonizing diet: healing by reclaiming traditional Indigenous foodways. Cuizine: The Journal of Canadian Nutrient Cultures. 2008;1(i):1–26.

-

Loppie Reading C, Wien F. Health Inequalities and the Social Determinants of Ancient Peoples' Health. Prince George: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2009.

-

Bombay A, Matheson Thou, Anisman H. The intergenerational effects of Indian residential schools: implications for the concept of historical trauma. Transcult Psychiatry. 2014;51(3):320–38.

-

Truth and Reconciliation Committee of Canada. They Came for the Children: Canada, Aboriginal Peoples, and Residential Schools. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; 2012.

-

About The states - Truth and Reconciliation Committee of Canada. http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/alphabetize.php?p=4. Accessed 27 Jan 2017.

-

Kirmayer LJ, Dandeneau S, Marshall E, Phillips MK, Williamson KJ. Rethinking resilience from Ethnic perspectives. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(2):84–91.

-

Evans-Campbell T, Walters KL, Pearson CR, Campbell CD. Indian boarding school experience, substance apply, and mental health among urban 2-spirit American Indian/Alaska natives. Am J Drug Alcohol Corruption. 2012;38(5):421–7.

-

Kirmayer LJ, Gone JP, Moses J. Rethinking historical trauma. Transcult Psychiatry. 2014;51(3):299–319.

-

Written report of the Majestic Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/webarchives/20071115053257/http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/ch/rcap/sg/sgmm_e.html. Accessed 25 Jan 2017.

-

Wesley-Esquimaux C, Smolewski M. Celebrated trauma and aboriginal healing. Ottawa, ON: Ancient Healing Foundation; 2004:i–110.

-

Archibald Fifty. Decolonization and Healing: Indigenous Experiences in the Unites States. Ottawa: Commonwealth of australia and Greenland; 2006.

-

Truth and Reconciliation Committee of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Committee of Canada; 2015.

-

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):xix–32.

-

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;five(one):69.

-

Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. Scoping the scope' of a cochrane review. J Public Health. 2011;33(1):147–l.

-

Wilson Chiliad, Immature TK. An overview of aboriginal health research in the social sciences: current trends and future directions. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67(two-3):179–89.

-

Immature TK. Review of research on ancient populations in Canada: relevance to their health needs. Br Med J. 2003;327(7412):419–22.

-

Stout R, Peters S. kiskinohamâtôtâpânâsk: Inter-generational Furnishings on Professional person First Nations Women Whose Mothers are Residential School Survivors. Winnipeg, MB: The Prairie Women's Wellness Centre of Excellence; 2011.

-

Commencement Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC): Showtime Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS) 2008/10: National report on adults, youth and children living in Start Nations communities. Ottawa, ON: FNIGC; 2012.

-

Wilson K, Rosenberg MW, Abonyi S. Aboriginal peoples, health and healing approaches: the furnishings of historic period and place on health. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(3):355–64.

-

Kaspar V. The lifetime result of residential schoolhouse attendance on Indigenous health status. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2184–90.

-

Hackett C, Feeny D, Tompa E. Canada'southward residential school system: measuring the intergenerational bear on of familial attendance on health and mental health outcomes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(11):1096–105.

-

Feir D. The Intergenerational Consequence of Forcible Assimilation Policy on Education. Victoria: University of Victoria; 2015.

-

Ghosh H. Urban reality of type 2 diabetes among Beginning Nations of eastern Ontario: western scientific discipline and Indigenous perceptions. J Global Citizenship Disinterestedness Educ. 2012;two(2):158–81.

-

Howard HA. Canadian residential schools and urban Indigenous cognition production nigh diabetes. Med Anthropol. 2014;33(half-dozen):529–45.

-

Dyck RF, Karunanayake C, Janzen B, Lawson J, Ramsden VR, Rennie DC, Gardipy PJ, McCallum L, Abonyi S, Dosman JA, et al. Do bigotry, residential schoolhouse attendance and cultural disruption add together to private-level diabetes risk among ancient people in Canada? BMC Public Health. 2015;xv:1222.

-

Cooke MJ, Wilk P, Paul KW, Gonneville S. Predictors of obesity among Metis children: socio-economic, behavioural and cultural factors. Tin can J Public Health. 2013;104(4):e298–303.

-

Healey K: Inuit parent perspectives on sexual health advice with boyish children in Nunavut: "it's kinda hard for me to attempt to observe the words". Int J Circumpolar Wellness. 2014;73:25070.

-

Healey GK. Inuit family understandings of sexual health and relationships in Nunavut. Tin can J Public Wellness. 2014;105(2):e133–137.

-

Varcoe C, Dick Due south. The intersecting risks of violence and HIV for rural aboriginal women in a neo-colonial Canadian context. J Aborig Health. 2008;4(one):42–52.

-

Craib KJP, Spittal PM, Patel SH, Christian WM, Moniruzzaman A, Pearce ME, Demerais L, Sherlock C, Schechter MT, Cedar Project P. Prevalence and incidence of hepatitis C virus infection among aboriginal young people who use drugs: results from the Cedar Project. Open Med. 2009;three(iv):e220–seven.

-

Walls ML, Whitbeck LB. Distress among Indigenous Northward Americans: generalized and culturally relevant stressors. Soc Ment Health. 2011;1(2):124–36.

-

Anderson T. The social determinants of college mental distress amid Inuit. Ottawa, ON: Statistics CanadaCatalogue no. 89-653-X2015007; 2015.

-

Stout R. Kiskâyitamawin Miyo-mamitonecikan: Urban Aboriginal Women and Mental Health. Winnipeg: Prairie Women's Health Centre of Excellence; 2010.

-

Elias B, Mignone J, Hall M, Hong SP, Hart L, Sareen J. Trauma and suicide behaviour histories amidst a Canadian Indigenous population: an empirical exploration of the potential role of Canada's residential schoolhouse system. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(x):1560–ix.

-

First Nations Regional Longitudinal Wellness Survey (RHS): First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey (RHS) 2002/03: Results for Adults, Youth, and Children Living in Kickoff Nations Communities. Ottawa, ON: Start Nations Centre; 2007.

-

Jacklin 1000. Diversity within: deconstructing aboriginal community health in Wikwemikong unceded Indian reserve. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(five):980–9.

-

Dionne D. Recovery in the Residential Schoolhouse corruption aftermath: A new healing epitome. Lethbridge: University of Lethbridge; 2008.

-

Chansonneuve D. Addictive Behaviours Amid Aboriginal People in Canada. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation; 2007.

-

Bombay A, Matheson Grand, Anisman H. Intergenerational trauma: covergence of multiple processes among First Nations people in Canada. J Aborig Health. 2009;five(3):6–47.

-

Kirmayer LJ, Tait CL, Simpson C. The mental health of aboriginal peoples in Canada: transformations of identity and customs. In: Kirmayer Fifty, Valaskakis GG, editors. Healing Traditions: The Mental Wellness of Aboriginal Peoples in Canada. Vancouver: UBS Press; 2009. p. 3–35.

-

Anderson T, Thompson A. Assessing the social determinants of self-reported Inuit health in Inuit Nunangat. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89‑653‑X2016009; 2016.

-

Barton SS, Thommasen HV, Tallio B, Zhang West, Michalos Air-conditioning. Health and quality of life of aboriginal residential school Survivors, Bella Coola Valley, 2001. Soc Indic Res. 2005;73(2):295–312.

-

Bombay A, Matheson Chiliad, Anisman H. The affect of stressors on second generation Indian residential school Survivors. Transcult Psychiatry. 2011;48(4):367–91.

-

Bombay A, Matheson K, Anisman H. Appraisals of discriminatory events amid adult offspring of Indian residential schoolhouse Survivors: the influences of identity axis and past perceptions of discrimination. Cultur Defined Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2014;20(1):75–86.

-

Chongo M, Lavoie JG, Hoffman R, Shubair G. An investigation of the determinants of adherence to highly agile anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) in aboriginal men in the Downtown Eastside (DTES) of Vancouver. Can J Aborig Customs-Based HIV/AIDS Res. 2011;four:32–66.

-

DeBoer T, Distasio J, Isaak CA, Roos LE, Bolton S-L, Medved M, Katz LY, Goering P, Bruce L, Sareen J. What are the predictors of volatile substance use in an urban community of adults who are homeless? Can J Commun Ment Health. 2015;34(2):37–51.

-

Dionne D, Nixon One thousand. Moving beyond residential school trauma corruption: a phenomenological hermeneutic analysis. Int J Ment Heal Aficionado. 2014;12(3):335–fifty.

-

Findlay IM, Garcea J, Hansen JG. Comparing the Lived Experience of Urban Ancient Peoples with Canadian Rights to Quality of Life. Ottawa: Urban Aboriginal Cognition Network; 2014.

-

Gone JP. Redressing Offset Nations historical trauma: theorizing mechanisms for Indigenous culture equally mental health treatment. Transcult Psychiatry. 2013;50(5):683–706.

-

Iwasaki Y, Bartlett JG. Culturally meaningful leisure equally a manner of coping with stress among aboriginal individuals with diabetes. J Leis Res. 2006;38(3):321.

-

Iwasaki Y, Bartlett J. Stress-coping among aboriginal individuals with diabetes in an urban Canadian city. J Aborig Health. 2006;3:xi.

-

Iwasaki Y, Bartlett J, O'neil J. An examination of stress among aboriginal women and men with diabetes in Manitoba. Canada Ethn Health. 2004;9(two):189–212.

-

Jackson R, Cain R, Prentice T. Depression among Aboriginal People Living with HIV/AIDS: Research Report. Ottawa: Canadian Ancient AIDS Network; 2008.

-

Jones LE. "Killing the Indian, Saving the Man": The Long-run Cultural, Wellness, and Social Effects of Canada's Indian Residential Schools. Ithaca: Cornell University; 2014.

-

Juutilainen SA, Miller R, Heikkilä L, Rautio A. Structural racism and Indigenous health: what Indigenous perspectives of residential school and boarding school tell us? A case study of Canada and Finland. International Indigenous Policy Journal.2014;5(iii):1–18.

-

Kral MJ. "The weight on our shoulders is also much, and nosotros are falling": Suicide among Inuit male youth in Nunavut, Canada. Med Anthropol Q. 2013;27(one):63–83.

-

Kumar MB. Lifetime suicidal thoughts among First Nations living off reserve, Métis and Inuit anile 26 to 59: Prevalence and associated characteristics. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89‑653‑X2016008; 2016.

-

Kumar MB, Nahwegahbow A. Past-year suicidal thoughts among off-reserve Starting time Nations, Métis and Inuit adults aged xviii to 25: Prevalence and associated characteristics. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89‑653‑X2016011; 2016.

-

Kumar MB, Walls M, Janz T, Hutchinson P, Turner T, Graham C. Suicidal ideation amid Métis adult men and women—associated gamble and protective factors: findings from a nationally representative survey. International Periodical of Circumpolar Health. 2012;71:18829. x.3402/ijch.v3471i3400.18829.

-

Lemstra M, Rogers Grand, Thompson A, Buckingham R, Moraros J. Take chances Indicators of depressive symptomatology among injection drug users and increased HIV hazard behaviour. Can J Psychiat. 2011;56(6):358–66.

-

Lemstra G, Rogers M, Thompson A, Moraros J, Buckingham R. Take chances indicators associated with injection drug utilise in the ancient population. AIDS Care. 2012;24(11):1416–1424 1419p.

-

Moniruzzaman A, Pearce ME, Patel SH, Chavoshi Due north, Teegee M, Adam W, Christian WM, Henderson E, Craib KJ, Schechter MT. The Cedar Project: correlates of attempted suicide amid young aboriginal people who utilise injection and not-injection drugs in 2 Canadian cities. International Journal of Circumpolar Wellness 2009;68(3).

-

Mota N, Elias B, Tefft B, Medved M, Munro Yard, Sareen J. Correlates of suicidality: investigation of a representative sample of Manitoba Kickoff Nations adolescents. Am J Public Wellness. 2012;102(seven):1353–61.

-

Oster RT, Grier A, Lightning R, Mayan MJ, Toth EL. Cultural continuity, traditional Indigenous language, and diabetes in Alberta Showtime Nations: a mixed methods report. Int J Equity Wellness. 2014;13:92.

-

Owen-Williams EA. The Traditional Roles of Caring for Elders: Views from Start Nations Elders Regarding Health, Violence, and Elder Abuse. Tennessee: Academy of Tennessee Wellness Science Center; 2012.

-

Robertson LH. The residential school experience: syndrome or celebrated trauma. Pimatisiwin. 2006;4(one):1–28.

-

Ross A, Dion J, Cantinotti Thou, Collin-Vézina D, Paquette 50. Impact of residential schooling and of kid abuse on substance use problem in Ethnic peoples. Addict Behav. 2015;51:184–92.

-

Rotenberg C. Social determinants of health for the off-reserve Beginning Nations population, 15 years of historic period and older, 2012. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89‑653‑X2016009; 2016.

-

Rothe JP, Makokis P, Steinhauer L, Aguiar W, Makokis 50, Brertton G. The office played by a erstwhile federal government residential school in a First Nation customs's booze abuse and impaired driving: results of a talking circle. Int J Circumpolar Wellness. 2006;65(iv):347–56.

-

Smith D, Varcoe C, Edwards Northward. Turning effectually the intergenerational touch of residential schools on aboriginal people: implications for wellness policy and practice. Tin can J Nurs Res. 2005;37(4):38–60.

-

Sochting I, Corrado R, Cohen IM, Ley RG, Brasfield C. Traumatic pasts in Canadian ancient people: further support for a complex trauma conceptualization? B C Med J. 2007;49(6):320.

-

Stirbys CD. Potentializing Wellness through the Stories of Female person Survivors and Descendants of Indian Residential School Survivors: A Grounded Theory Study. Ottawa, ON: University of Ottawa; 2016.

-

van Niekerk K, Bombay A. Risk for psychological distress among cancer patients with a familial history of Indian residential school omnipresence: results from the 2008-10 Outset Nations Regional Health Survey. Psychooncology. 2016;25(SP. S3)):iii–3.

-

Walls ML, Hautala D, Hurley J. "Rebuilding our community": hearing silenced voices on aboriginal youth suicide. Transcult Psychiatry. 2014;51(ane):47–72.

-

Wardman D, Quantz D. An exploratory study of binge drinking in the ancient population. Am Indian Alaska native ment health res. 2005;12(one):49.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Courtney Waugh, who reviewed our search strategy and recommended valuable databases to use in our scoping review. Additionally, the authors would also like to acknowledge the valuable feedback and comments provided by the members of Ethnic organizations and communities: The Indigenous members did non wish to exist identified.

Funding

Funding for this manuscript was provided past The Western Libraries Open Access Fund. AM and Prisoner of war are as well funded past the Children's Health Foundation through the Children'due south Heart Health grant.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

AM conducted the database searches. Pow and AM reviewed the abstracts and extracted relevant information from included studies. All authors contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and canonical the last manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Writer information

Affiliations

Respective writer

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is distributed nether the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/), which permits unrestricted apply, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/nada/1.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Wilk, P., Maltby, A. & Cooke, M. Residential schools and the effects on Indigenous health and well-being in Canada—a scoping review. Public Wellness Rev 38, 8 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0055-six

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0055-6

Keywords

- Residential schools

- Indigenous health

- Wellness

- Colonialism

- Historical trauma

Source: https://publichealthreviews.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40985-017-0055-6

0 Response to "Articles for Negative Effects of Mental Health on Families and Communities"

Publicar un comentario